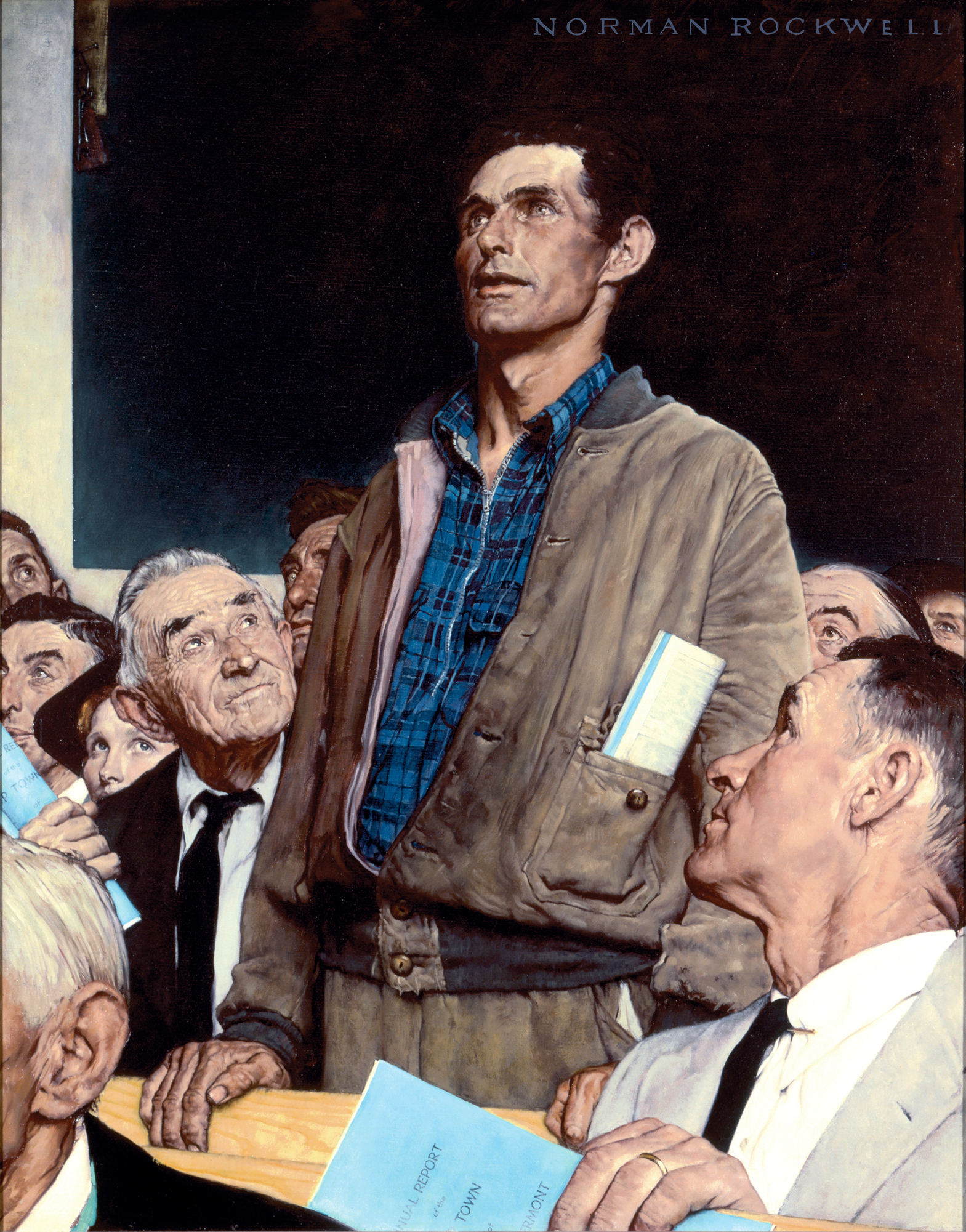

Education, communication and political science have greatly improved since 1857

Iowa’s Nov. 3 ballot includes a statewide referendum asking Iowans if they want to call a state constitutional convention. If Iowans vote yes, Iowa’s Constitution grants them two more votes: to elect delegates to a convention and then to vote up or down any amendments the convention proposes. Iowans have called three conventions, the last one in 1920. Iowans called a fourth in 1933, but that was a state convention to amend the U.S. Constitution, not Iowa’s Constitution.

Until 1857, the only way to amend Iowa’s Constitution was via constitutional convention. At Iowa’s 1857 constitutional convention, Iowa’s framers granted the Legislature the power to propose amendments directly without first calling a convention. But they didn’t want to give the Legislature a monopoly over the proposing of amendments, as incumbent legislators could use that power to veto proposed amendments that might reduce their own power while improving Iowa’s democracy. So the framers created a second amendment process, the decennial constitutional convention referendum, which would allow the people to propose amendments without the Legislature’s approval.

Ever since, the Legislature and the special interests that wield disproportionate power over it have hated this legislative bypass process. Without explicitly rebutting, let alone acknowledging, the framers’ arguments for including a legislative bypass process in Iowa’s Constitution, they have acted as if it were self-evident that any amendment process outside their control would harm rather than help democracy in Iowa.

I agree with Iowa’s framers that the convention process is necessary to address the types of issues where incumbent legislators and their allies have a blatant conflict of interest with their constituents, including election processes (e.g., legislative redistricting, term limits, and campaign finance), the relative powers of competing branches of government (e.g., executive and judicial), and rights the people reserve to themselves (e.g., speech and privacy). But I also believe that convention opponents have a point when they assert that Iowa’s current convention process isn’t perfect.

Most of the states that adopted the periodic constitutional convention referendum did so after Iowa, and some made improvements to the process. Most notable are procedures, like New York adopted in 1894, to reduce a legislature’s control of the enabling act. But those enhancements are inadequate to bring legislative bypass mechanisms into the modern age. Here I will propose just one reform to improve the process, which because it would make the process more democratic and effective, the Legislature would never propose on its own, thus also demonstrating the framers’ wisdom in creating a legislative bypass process.

In the current process, after a convention proposes constitutional amendments, the voters must ratify them before they become law. I recommend inserting between those two stages of the process an additional stage for popular participation and deliberation. I call the proposed new stage a “post-convention jury.”

The jury would consist of hundreds of Iowans randomly selected and stratified by at least gender and geography; for example, the jury could consist of a randomly selected male and female from each of Iowa’s 100 General Assembly districts. The jury would be selected and moderated by a three-member panel of judges appointed by Iowa’s Supreme Court. Representatives of the delegates who voted pro and con on each proposed amendment would present the pro and con debate before.

To avoid onerous travel, the jurors would convene remotely via the various local courthouses spanning Iowa. Over a period of at least one hour per proposed amendment, the jury would listen to the pro and con sides debate and then vote each amendment up or down. The resulting tally, with an accompanying link to a video recording of the actual debate, would be printed on each ballot and serve an analogous information function to the political party labels on the ballot next to the names of candidates. Currently, there is no such information cue to help voters decide when they vote on referendums. The next convention could implement key elements of such an educational institution even if it wasn’t part of the Legislature’s enabling act.

Regardless of political party affiliation, Americans in recent decades have become increasingly mistrustful of their fellow citizens’ capacity for democracy, including their capacity to play their designated roles in state constitutional democracy. This mistrust is a tragedy, as trust in the democratic reform process is essential to maintaining the long-term health of a democracy. It is also ironic, given the great improvement since 1857 in Iowans’ level of education, means of communication, and access to state-of-the-art political science. Instead of allowing the political establishment to exploit Iowans’ mistrust of each other to preserve the status quo, we should seek to fix our democratic processes with the same can-do attitude that Iowa’s framers had.

#

J.H. Snider, a former fellow at Harvard University’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, is the editor of The Iowa State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse and author of “Does the World Really Belong to the Living? The Decline of the Constitutional Convention in New York and Other US States, 1776–2015.” His Iowa Con Con 101 provides a short video explainer of the convention process.

Source: Snider, J.H., Iowa’s constitutional convention process, a triumph of democracy, could be improved, The Gazette, October 10, 2020.