The Iowa State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse

This website provides news, pro & con, historical, and other information related to Iowa's constitutionally mandated November 3, 2020 referendum on whether to call a state constitutional convention.

Introduction

It restricts the following critiques to mainstream media articles. The ≈ ratings were inspired by the Washington Post’s Pinnochio. ratings. One (≈) to two (≈≈) is for an unbalanced account with no outright falsehoods. Three (≈≈≈) is for an outright falsehood. Two (≈≈) is for so unbalanced and out of context as to be essentially false. One (≈) is for contestable by a well-informed reasonable person.

I decided to produce this fact check because Iowa’s press has published so many blatantly incorrect or simply one-sided factual statements about Iowa’s constitutional convention history, and the errors have been republished decade after decade, perhaps because reporters and other opinion leaders have viewed previously published reports as authoritative sources.

Please understand that in providing such ratings I do not intend to imply any malicious intent by reporters. But I do intend to suggest a lack of appropriate due diligence.

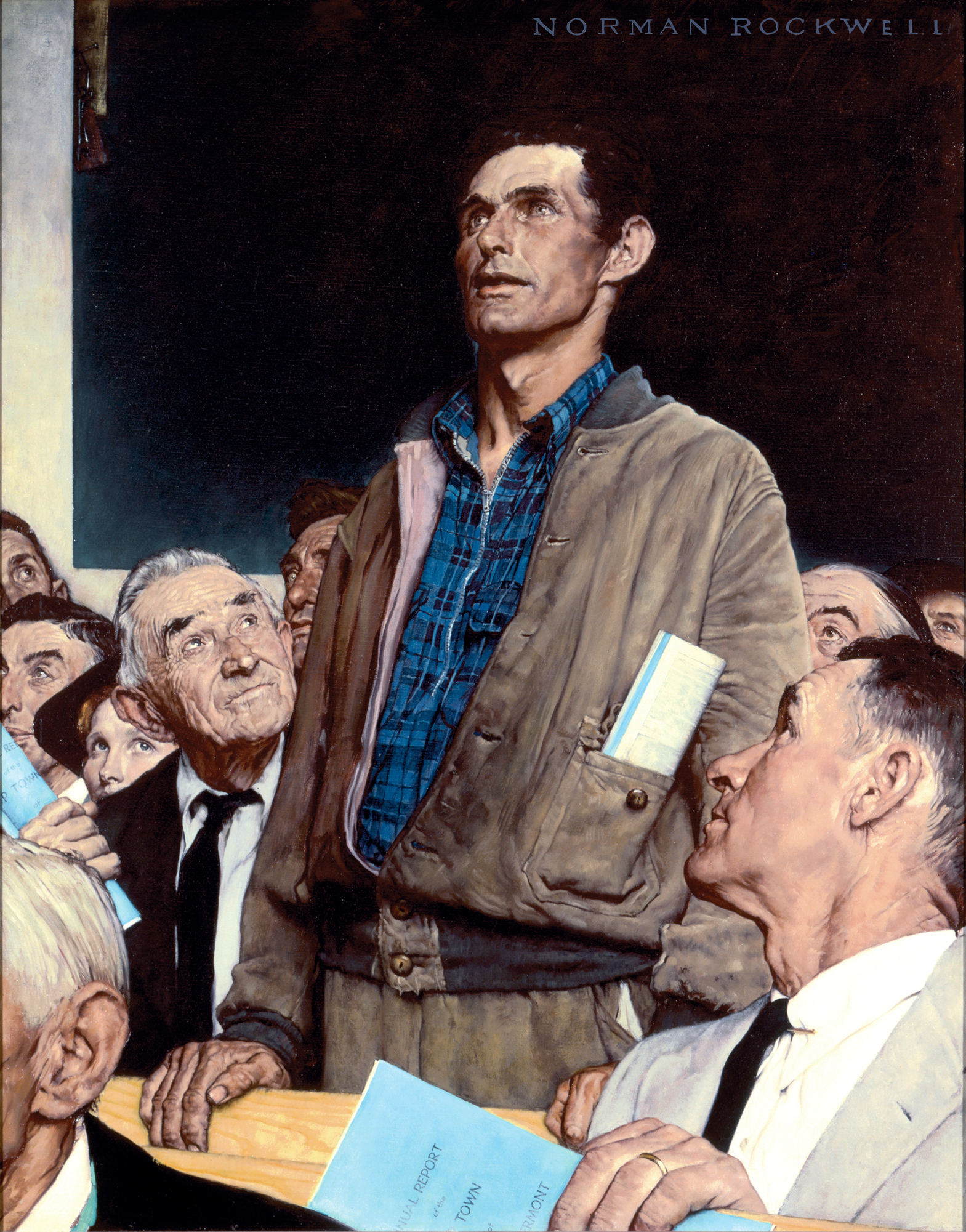

–J.H. Snider, Editor

The Iowa State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse

Articles

Des Moines Register

Gruber-Miller, Stephen, Should Iowa hold a constitutional convention? It’s on the ballot this year, Des Moines Register, October 2, 2020. News Section.

“Since 1970, the Iowa Constitution has required that every 10 years, the state must place a measure on the ballot asking Iowans if they support holding a constitutional convention to propose amending the state’s Constitution.”

≈≈ On October 16, 2020, the Des Moines Register corrected this misleading statement and issued a correction at the bottom of its article.

This assertion is also found in a widely used textbook on Iowa government. But it is incorrect. The decennial referendum was included in Iowa’s 1857 Constitution and has been on the ballot every ten years since 1870. It is true that when the Constitution’s amendment clause was cleaned up in 1964 the date of the next referendum was changed from 1870 to 1970, but the decennial referendum by then already had a 100-year history. Somebody writing that textbook may have simply read the Constitution as it currently exists and didn’t know its history. Others who may have fact-checked by reading the Constitution may have merely reinforced this error in their minds. Other articles published in recent decades on the convention referendum have the same error. For the results of the referendums since 1870, see the “Data” submenu under the “History” menu on this website.

“That year, there was an unsuccessful push to hold a convention with the goal of amending Iowa’s Constitution to ban same-sex marriage, which the Iowa Supreme Court had legalized the year before.”

≈

The problem with this statement is more subtle and reflects the spin state legislators and other trusted inside sources provide to the press. There was no substantial push that year for a convention, and the convention opponents that year hyped the same sex marriage issue as the face of convention advocates because it’s politics 101 to make the face of your opposition an unpopular cause.

“If the measure is approved, the Iowa Legislature must create rules for the election of delegates to the convention and a process for submitting any constitutional amendments proposed by the convention to the people for a vote.”

≈

Technically true, but the reason state legislators hate state constitutional conventions—and the reason Iowa’s framers put this provision in Iowa’s Constitution—is because a convention is a serious check on a legislature’s power, as it takes away its gatekeeping power over constitutional amendment. The focus of this statement is on the Legislature’s ability to control the process rather than the significant constraints on that control, which has been the primary reason for the Legislature’s consistent and strong opposition to calling for a convention.

“The last time the measure was on the ballot, in 2010, it failed to pass by a two-to-one ratio.”

≈

Accurate history. But why not also observe the three and arguably four times the convention referendum did pass in Iowa history?

Advocates of the status quo in both dictatorships and democracies use this type of argument to discourage their opposition. For example, in Russia and China, the reigning dictators use this style of argument to discourage the democratic opposition by showing that their cause is hopeless, as most people aren’t interested in wasting their effort on hopeless causes.

The press should be focusing on the merits of the convention process. Using past popularity as a proxy for merit is a lazy form of argument, akin to an ad hominem attack. The press should explain why the framers included the referendum in Iowa’s Constitution and then discuss whether their reasoning was faulty or at least inappropriate to current circumstances.

We Are Iowa

Schlesselman, Hollie, Your 2020 ballot, explained: Judicial retention elections and constitutional convention, We Are Iowa, September 16, 2020. IowaConCon.info called We Are Iowa four times and spoke to two different producers between Sept. 18 and Oct. 23 to correct the first error concerning the 1970 claim. As of Oct 28, We Are Iowa had refused to make a correction.

“’Good government reforms that went into effect in the 1960’s among them a requirement that this would appear on the ballot every 10 years,’ Caufield said. ‘The question has been on the ballot since 1970.’”

≈≈

This assertion is also found in a widely used textbook on Iowa government. But it is incorrect. The decennial referendum was included in Iowa’s 1857 Constitution and has been on the ballot every ten years since 1870. It is true that when the Constitution’s amendment clause was cleaned up in 1964 the date of the next referendum was changed from 1870 to 1970, but the decennial referendum by then already had a 100-year history. Somebody writing that textbook may have simply read the Constitution as it currently exists and didn’t know its history. Others who may have fact-checked by reading the Constitution may have merely reinforced this error in their minds. Other articles published in recent decades on the convention referendum have the same error. For the results of the referendums since 1870, see the “Data” submenu under the “History” menu on this website.

“It’s been 163 years since Iowa had a constitutional convention, and that’s when the current constitution came to be.”

≈

Arguably technically true, but also misleading. First, Iowa has convened three conventions, and it’s not clear why only the most recent one should be mentioned. Second, when state constitutional conventions are usually referred to, they refer to the type of state constitutional convention intended here. On the other hand, Iowa held a state constitutional convention in 1933 to ratify the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, so as phrased this statement is arguably incorrect. Third, there is a big difference between calling and convening a convention. Iowa has convened three, definitely called four, and arguably called five–even excluding the 1933 state constitutional convention. As for the discrepancy, Iowans called a state constitutional convention in 1920. Then, Iowa’s Legislature violated Iowa’s Constitution by not convening it. In a Gore v. Bush type of recount situation, Iowans also arguably called one in 1900. Given that few Iowans may be aware of the distinction between calling and convening a convention–and the question on the ballot is whether to call one–this statement without appropriate context is misleading.

Iowa Public Radio

Sostaric, Katarina, Iowa’s 2020 ballots contain constitutional convention question, Radio Iowa, October 9, 2020.

”The state’s original — and only — constitution was ratified in 1857”

≈≈≈

No, Iowa became a state in 1846 and its first statehood constitution was ratified in 1846.

“It’s really the thing to do only if you think the system is fundamentally broken and needs to be changed in lots of ways.”

≈≈

That’s not the way the framers’ of Iowa’s 1857 Constitution conceived of the decennial periodic constitutional convention referendum that they proposed adding to Iowa’s 1846 Constitution. Just as the 1857 convention at which the framers’ modified Iowa’s 1846 Constitution proposed only relatively minor amendments to Iowa’s existing 1846 Constitution, a future convention need not make radical changes to be a success. Indeed, as Iowa’s 1857 framers conceptualized the democratic function of the decennial periodic constitution convention referendum, its primary function wasn’t to make radical changes; it was to provide a legislative bypass mechanism for proposing constitutional amendments for the voters to vote up or down.

“They can change anything in our constitutional system—about the courts, the legislature, the judiciary, how much money cities can borrow, what our individual rights are. So we’re really opening up a Pandora’s Box.”

Convention opponents often make this argument. But it’s unclear exactly what it means. For example, supreme courts can theoretically make any changes they want to a constitution without facing the electorate, especially if they have a lifetime appointment. (Former President Wilson even called the U.S. Supreme Court a “sitting constitutional convention”–without the ratification check a real convention would have.) And legislatures, like conventions, can propose any constitutional amendments they want, subject to the same type of up or down vote by the public. So it would seem that there is a double standard being applied to constitutional convention proposals as opposed to legislative proposals.

Also noteworthy: whereas the Iowa Legislature can pass any statutory law, subject to the Governor’s veto, it wants, an Iowa state constitutional convention can only propose laws. Many of the worst-case scenarios applied to an Iowa constitutional convention could just as easily be applied to the Legislature, except that the public gets a veto on convention but not Legislature proposals.

There is also the question of what type of Pandora’s Box is really being referred to here. For legislatures and groups that excel at influencing legislatures, a convention is, by definition, a Pandora’s Box because a convention forces them to give up control over the constitutional amendment proposal process. For voters, the alternative to a “Pandora’s Box” is a useless legislative bypass process because if the legislature can control a convention’s agenda, then the primary contemporary democratic rationale for convening a convention in a state without the citizens’ constitutional initiative is nullifed. That is, from a democratic theory perspective, the lack of legislature control is the prime feature–and thus not a bug–of the convention process.

Estherville News

Peterson, Amy, Flip the ballot over, Estherville News, October 11, 2020.

“The state’s original — and only — constitution was ratified in 1857 and it includes a requirement that voters be asked every 10 years if they wish to hold a constitutional convention to consider changes to the document.”

≈≈≈

No, Iowa became a state in 1846 and its first statehood constitution was ratified in 1846. This is a vivid illustration of how newspaper reporting can not only be factually wrong but copy the same incorrect facts from other newspapers–not only during the current election cycle but decade after decade as reporters copy the same story lines as earlier reporters and reveal their ignorance of Iowa’s Constitution and constitutional history.

“Since 1970, when the question was placed on the general election ballot….”

The decennial referendum was first placed on a general election ballot, as required by the 1857 Constitution, in 1870.

≈≈≈

KIWA Radio

Every 10 Years Iowa Voters Vote Yes Or No On Constitutional Convention, KIWA Radio, October 9, 2020.

“Whatever [the convention delegates] propose, whatever document they come up with, gets sent out to the people of Iowa to be voted on in one up or down vote.”

≈≈

No, a convention does have the option of combining its recommendations into a single document and then having the voters vote it up or down in a single vote. But they need not and often do not, especially in post-statehood constitutional conventions, including Iowa’s 1857 constitutional convention, which divided its non-controversial and controversial proposals into different documents so the latter wouldn’t sink the former. Often post-statehood conventions will propose many narrowly targeted amendments, sometimes dozens.

The Messenger

Decious, Elijah, Constitutional convention question on this year’s ballot, The Messenger, October 15, 2020. See Fact Check for an analysis of this article.

“The original Iowa Constitution that stands today was ratified in 1857, 11 years after Iowa became a state.”

≈≈≈

No, the original statehood constitution was ratified in 1846. And previously Iowa was ruled by organic acts, which are essentially constitutions.

“The ballot question is one short cut to amending the state’s constitution. Amendments can also be proposed through the Iowa Legislature.”

≈≈

Iowa’s 1857 constitutional framers created the legislatively initiated amendment process largely because they thought the previous process that only allowed amendment via constitutional convention was too difficult for minor amendments. That was also the most common justification used in other states to create the legislatively initiated amendment process. This passage turns that reasoning on its head. Comparing Iowa’s two-vote requirement to pass an amendment to Iowa’s constitutional convention process is like comparing apples and oranges, as the latter process requires at least three different types of votes to get proposals on the ballot: a referendum to hold a convention, a candidate election to elect candidates to the convention, and then a vote by the convention to place an amendment on the ballot for an up or down vote. Both amendment processes end the same way with a ballot referendum, but most observers believe the convention process is hardly a shortcut. Moreover, the article’s implications that 1) the purpose of a convention is a shortcut, completely misses the intent of Iowa’s framers to create a legislative bypass amendment mechanism (although it does capture the spin of convention opponents), and 2) a convention would short circuit public deliberation (although this, too, captures the spin of convention opponents), betrays ignorance of how Iowa constitutional conventions have worked in the past, including its 1857 convention, and would be expected to work in the future.

The Gazette

Lynch, James, Why are Iowa voters being asked about a constitutional convention? What checking this box means, The Gazette, October 17, 2020. On October 20, The Globe Gazette corrected in its online edition its factually incorrect statement: “Only once in state history, in 1920, have Iowans voted in favor of a constitutional convention.” The correction: “Iowa voters have approved ballot measures calling for a state constitutional convention three times — in 1844, 1856 and 1920.” On October 26, The Gazette corrected the original language in its online edition but with different wording.

“Only once in state history, in 1920, have Iowans voted in favor of a constitutional convention.”

≈≈≈

No. Iowans have unambiguously voted three times to call a state constitutional convention, 1844, 1856, and 1920, and arguably also in 1900. If the 1933 call for an Iowan state constitutional convention to ratify the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is added, that’s arguably five convention calls approved.

The definition of “Iowans” used above also excludes when the legislature called a convention without bothering to ask Iowans for their approval. For example, in 1846 the Legislature called a convention without bothering to ask the voters if they wanted one. The Legislature’s choice of rules has an extra political twist because two of the previous three times the Legislature put the question on the ballot the voters refused to call a convention. Since the Legislature claimed to represent “Iowans,” it asserted it didn’t need to ask them whether to call a convention. Under this definition of Iowans, Iowans have arguably approved six Iowan state constitutional conventions.

As an aside, two other convention calls have received more than 48% of the vote and four others have received more than 45%. And this was despite overwhelming opposition by Iowa’s political elites.

This false claim was made in the subheading of the Sunday print edition of The Gazette on page 1, top-of-fold. It is especially disturbing because claims about the unpopularity of convention calls have been the signature dog whistle of Iowa’s state constitutional convention opposition for many decades.

“Arguably, it [Iowa’s periodic constitutional convention referendum] does have a 19th century feel to it,” said Shelley, who has been teaching American government, public policy and voting behavior at ISU since 1979.

≈

Not to those who are students of legislative bypass mechanisms. Throughout the 20th Century, the highly regarded and influential National Municipal League endorsed the periodic constitutional convention referendum in its model state constitution. And the Initiative & Referendum Institute continues to report overwhelming popular support throughout the United States for the citizens’ initiative, including in the states that have it. It’s true that Iowa’s framers included the constitutional convention referendum in its 19th Century constitution, its 1857 Constitution. But neither type of legislative bypass institution–the periodic constitutional convention referendum (14 states), nor its close sibling, the citizens’ constitutional initiative (18 states)–was primarily a creature of the 19th Century. The push for such legislative bypass mechanisms primarily came in the 20th, not the 19th, Century; more than three quarters (76%) of the U.S. states that have a legislative bypass mechanism to propose constitutional amendments adopted the provision in the 20th Century.

KHQA-TV

Raub, Amber, Beyond the Podium: Iowa Constitutional Convention, KHQA-TV, October 25, 2020.

“This amendment was written into the Iowa Constitution in 1850 as something to be asked every 10 years.”

≈≈≈

No. It was both proposed by a constitutional convention and ratified by voters in 1857.

“‘They keep voting it down so one has never actually been held,’ Coffey said.”

≈≈≈

Iowa has held three state constitutional conventions. Four if the 1933 state constitutional convention to propose ratification of the U.S. 21st Constitutional Amendment (overturning prohibition) is counted.

“‘Changing a constitution at a constitutional convention is extremely difficult. You would have to have an amendment that had broad-level support, over 2/3rd’s of republicans and democrats, and that almost never happens,’ Coffey said.”

≈≈≈

Coffrey is confusing, as he appears to do several times in this interview, the federal and Iowa constitutional provisions concerning constitutional conventions. An Iowa state constitutional convention can propose constitutional amendments with a simple majority and Iowa voters then have an opportunity to vote those proposals up or down also with a simple majority.

Iowa Labor News

Backside of the Ballot: A Constitutional Convention – Yes or No, and What are the Consequences?, Iowa Labor News, October 27, 2020.

“This provision, which can be found in Article X, Section Three of the Iowa Constitution has been in the constitution since its inception in 1857 and was reset in 1970 to have the question asked every ten years thereafter.”

≈≈≈

No and no. Iowa’s first statehood constitution was ratified by voters in 1846, and the decennial constitutional convention referendum has been mandated in Iowa’s Constitution since 1857.

“Right now, if a constitutional convention were to be held, anything and everything contained in our constitution would and could be subject to change and revision.”

≈≈≈

No, all federal law is superior to Iowa law, including the U.S. Constitution’s “Bill of Rights.” A convention could not propose and the people ratify any law inconsistent with federal law.

“The Legislature would appoint the convention delegates.”

≈≈≈

No. The people of Iowa elect the delegates to a convention.

“Here is what we know about the process… you should know the facts about this question on the ballot.”

≈≈

Basic facts about the process are indeed very important. But this article made numerous mistakes about easy to ascertain facts about the process–and all skewed in a direction that would foster opposition.

We Are Iowa

Schmillen, Jackie, Verify Your Vote: Answering top Iowa election questions, We Are Iowa, October 30, 2020.

“This question has been on your ballot since 1970….”

≈

It has been on the ballot since 1870, one hundred years before 1970, as part of a decennial referendum. It actually first appeared on the ballot in 1840 (and again in 1842 and 1844) when the Legislature wanted to call a state constitutional convention to propose a statehood constitution, which ultimately passed in 1846. We Are Iowa did a better job this time than last time in its reporting. But its deep-seated resistance to making corrections is the type of behavior that sometimes gives journalists a bad name.

House Republican Newsletter

Constitutional Convention on the Ballot, House Republican Newsletter, October 29, 2020.

“There is another way Iowans can amend the constitution, without a full constitutional convention. If a proposed constitutional amendment passes two consecutive general assemblies, the amendment is placed on the state ballot where Iowans can decide if they want the amendment or not. This is a much simpler process and wellestablished way of amending the Constitution.”

≈≈

This is a typical type of one-sided account by convention opponents, as it fails to explain why Iowa’s Framers included this second amendment mechanism in Iowa’s Constitution while implying that the first one, the Legislature controlled amendment process, only has advantages in comparison to the second one.

Des Moines Register

Gruber-Miller, Stephen, Iowans to vote up or down on convention to amend the Iowa Constitution, Des Moines Register, November 2, 2020.

This article is largely a replica of the one published on Oct. 2, 2020 and critiqued above. The correction noted above was made, but the article itself remained overwhelmingly one-sided in its framing. Here is J.H. Snider’s comment, posted on the article itself:

Gruber-Miller appears to have relied too much on his statehouse buddies, all of whom hate the constitutional convention process, as sources in researching this “news” report. His article is full of the standard tropes used by convention opponents to disparage the convention process. Perhaps most noteworthy, he either purposely chose to ignore or is clueless as to why Iowa’s Framers included the convention process in Iowa’s 1857 Constitution: it was largely to provide a mechanism for the people of Iowa to bypass incumbent legislators and the groups who excel at influencing them, who would otherwise have monopoly gatekeeping power over the proposal of constitutional amendments. Gruber-Miller doesn’t have to agree with the Framers, but it is professionally irresponsible for him not to acknowledge their arguments before steamrolling them. In Gruber-Miller’s one-sided, anecdotal telling, the convention process has no notable advantages over the Legislature initiated constitutional convention process while likely leading to the passage of unpopular amendments like the ones he cites. If the Des Moines Register had published Gruber-Miller’s article in the opinion pages, I would have had no problem with it. But, in my judgment, publishing it in the news pages was professional malpractice.

This version of Gruber-Miller’s article closely follows his original Oct. 2 version. But it does remove the blatant factual error in the Oct. 2 version concerning Iowa’s constitutional convention history. That factual correction by the Des Moines Register should be commended.

Search This Website