The Iowa State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse

This website provides news, pro & con, historical, and other information related to Iowa's constitutionally mandated November 3, 2020 referendum on whether to call a state constitutional convention.

Copied below are selected remarks arguing for a periodic constitutional convention referendum by Delegate James C. Traer and others at Iowa’s 1857 constitutional convention.

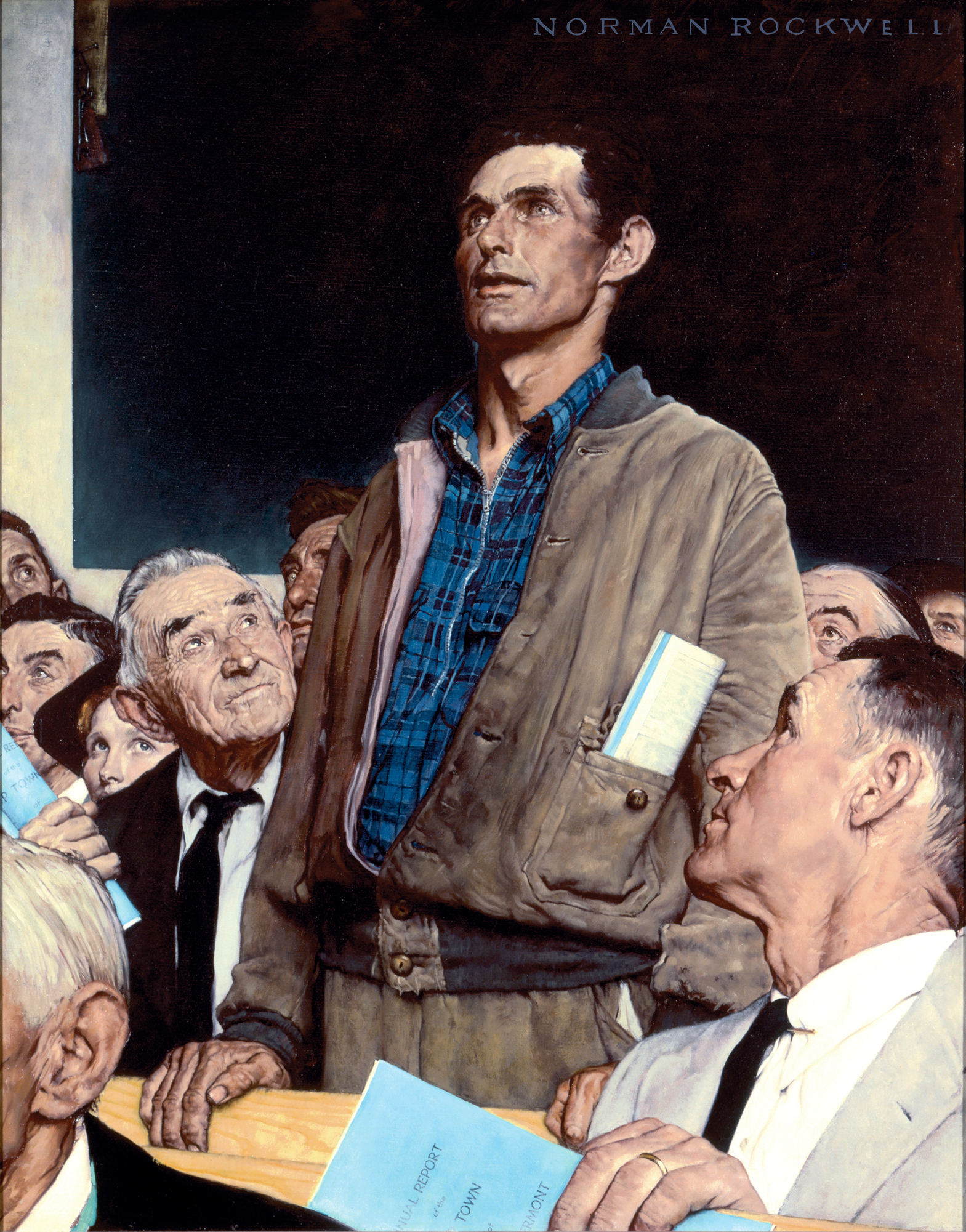

James C. Traer

Traer was born in 1825, and lived in Muscatine County, Cedar County, and Cedar Rapids before moving to Benton County 1851, where he was one of the earliest settlers. He was a member of Iowa’s 1857 Constitutional Convention. Prior to the convention, he was a doctor. Afterwards, he became a lawyer and mayor. At the Convention, his comments were the earliest and most eloquent in arguing the case for including a periodic constitutional convention section in Iowa’s constitution. In Iowa’s statehood constitution, the only way to amend Iowa’s constitution was via a Legislature initiated constitutional convention. The Convention’s proposed constitution would allow Legislature proposed constitutional amendments, which would reduce the Legislature’s incentive for calling an independent constitutional convention whose proposed constitutional amendments the Legislature would have more trouble controlling. Traer argued it was vital that the people of Iowa have an institutional mechanism to bypass the Legislature’s gatekeeping power over constitutional reform, although he used different terminology as quoted below.

Second to Traer in eloquence was John T. Clark. Clark captures the majority view that the periodic constitutional convention referendum is necessary to prevent Iowa’s Legislature from having monopoly power over constitutional amendment proposals. But in Traer we sense someone who thought much more deeply and passionately about the unique problem of constitutional amendment; that is, someone who better understood the democratic and political logic of the periodic constitutional convention in the practical context of a state constitution.

Traer was a member of the Distribution of Powers (Checks & Balances) Committee. John T. Clark and David Bunker were members of the Committee on Amendments to the Constitution.

Mr. TRAER offered the following resolution:

Resolved, That the committee to whom was referred so much of the Constitution as refers to amending the same be instructed to enquire into the expediency of so amending the Constitution as to provide for a vote for or against holding a Convention to amend the Constitution at least once in ten years.

I look upon this question as one of the most important that can come before this Convention, involving, as it does, the rights of the people to a greater extent than any question that has been or can be presented here. I am a little surprised that my friend from Wapello [Mr. Gillaspy] should take the position he now does, as I believe he has invariably been upon the side of the people heretofore. Now he comes in and tells us it is dangerous to submit this question to the people, as they might possibly vote in favor of something that would prove ruinous to the interests of the State. This is a different kind of logic from that which the gentleman has generally used when speaking of the rights of the people; and I must say that it is a new kind of democracy to me….

I hold that the people have an inherent right to change their fundamental law at any time without their representatives or any other body interfering with that right. I believe that the general principle laid down and generally acted upon in these cases, is that, if there is an article upon amendments placed in the Constitution; or, in other words, if there is any provision here that does not expressly give the people the right to amend their Constitution without the action of the Legislature, it leaves the people subject to the action of the Legislature, or, in other words, they have not the right to amend their Constitution independent of the Legislature.

I am perfectly willing that the Legislature, as is provided in the first section, shall have the right to change the Constitution. But, at the same time, I desire to have the question so shaped that the people can have a Convention, without the Legislature having anything to do about it.

The amendments committee at the 1857 constitutional convention had five members. David Bunker was one of the three members in the majority who drafted the majority report, including the periodic constitutional convention referendum.

In regard to the second section ‘of this report, which provides for submitting the question of a constitutional convention to the people, I believe the committee were of the opinion that, under our form of government, all rights should be retained inherent in the people, and they should have the power to act upon their fundamental law, without the intervention of anybody whatever. And we thought ten years would be a proper period of time for a submission of this question directly to the people….

The object of the first section is to secure amendments to the constitution, without the expense of calling a convention, and the object of the second section is to reserve to the amendments being submitted to the people the right to alter the fundamental law, without the intervention of any other power.

What I am in favor of is an arrangement by which the people can amend the constitution at any time, without applying to the legislature in any shape or form. That is my position. I wish to leave it entirely to the people. And I wish to put some provision into the constitution to prevent the legislature from assuming the right to deprive the people of the right to say when and where and how they will amend their constitution.

The amendments committee at the 1857 constitutional convention had five members. John T. Clark was one of the three members in the majority who drafted the majority report, including the periodic constitutional convention referendum.

I am willing to place to the greatest extent the control of the fundamental law, the foundation of all the law of our State, in the hands of the people, and independent of any power of the legislature to control their will. I am unwilling to place the constitution of the State out of the direct control of the people, out of their reach, in the hands of a representative body. I believe it should be retained in their possession, within their control, that they should have the privilege themselves to reach that question, without the necessity of legislative enactment. The experience of the past proves the necessity of it. I think that there might be a case in this State in which it would be necessary perhaps to use that power, and when the legislative body might refuse to call a convention in accordance with the wish of the people…. The people had their constitution formed in the early days of our history, before we had had much experience in a republican form of government, and they had failed to reserve to the people themselves the right of calling a convention, except through the legislative bodies…. I think all power should be inherent in the people, and that they should have the right to reach the fundamental laws of their land without being compelled to ask it as a privilege from the hands of any legislative body. I am in favor of what the gentleman has been talking about heretofore; I am in favor of making the people directly the controllers of the government; of allowing them, themselves, without asking it as a favor of their legislative bodies the right to say when they will change, alter, or modify their constitution.

I believe we all agree upon one question, that the people are the source of power; or, in other words, that all political power was originally vested in the people of this government. If that be the case, and we are all agreed upon that that point, then the question arises–how, or in what way, are we going to delegate this power…? I hold that we should do the same, as any individual would do, when he makes another individual his agent to carry out certain prescribed objects: reserve the right of countermanding the authority we give our agents at any time we may see fit. That is just what I desire to do in the constitution….

When we have agents to act for us, I hold it is a contradiction in terms that we should give them the right to say when we may or may not act.

As I said before, the only question that arises is this: Can the people of the State of Iowa–after we have made this Constitution and placed the article in it which gentlemen here propose–amend it without the authority or consent of those whom they have delegated to represent them in the legislature? I hold that they can.

We have a provision for amendments by the legislature, and if we retain the provision for a vote of the people once in ten years, that will give them the power to hold a convention independent of the legislature; they can vote upon the question every tenth year, whether the legislature will it or not, whether they shall hold a convention to revise the constitution.

I am in favor of retaining the provision in the constitution which places the people above their representatives, which places them above and independent of their legislature, upon the question of the revision or amendment of the constitution; that they may at all times retain in their own hands that power, and not be dependent upon any other power for it…. The people should have the right of amending or altering the constitution, and as there may be a case in which they cannot obtain the desired legislative enactments, I think there should be left in the constitution a provision giving them that right. The legislature may have some outside pressure, and may not represent the wishes of the people.

On motion of Mr. TRAER,

The report was ordered to be engrossed for a third reading and referred to the committee on revision.

In arguably one of the greatest shortsighted debates in constitutional convention history, Traer tried to get the convention to move beyond the relatively short and vague language for implementing a periodic constitutional convention referendum that New York had pioneered in 1846 and was the basis for much of Iowa’s proposed constitution. In this, Traer was fifty years ahead of his time. It wasn’t until New York experienced in the 1890s something similar to what Iowa went through in 1920 that Traer type language became the benchmark for a well-designed periodic constitutional convention referendum that would head off Iowa 1920-style legislature shenanigans.

Traer twice introduced his proposed amendment to the periodic convention clause—once near the end of the major debate on February 19, 1857 regarding the future amendments article and then once again in the relatively short discussion on February 20 regarding the same article. In both cases, it is clear from the discussion that the delegates didn’t think his add-on was necessary. They thought the ten year periodic amendment referendum inherently allows the people to bypass the Legislature’s gatekeeping power over amendment, just as the requirement for periodic legislative sessions—essential to America’s system of checks & balances—inherently allows the legislature to bypass the governor’s power to call or prorogue state legislatures (a huge problem in 18th Century colonial America).

Traer’s proposal is no longer state-of-the-art language to ensure independence from the legislature in executing the periodic constitutional convention referendum process. But in 1857 it would have made Iowa a leader rather than follower among the handful of mid-19th Century states, beginning with New York in 1846, starting to include periodic constitutional convention referendum clauses in their state constitutions.

On March 5, 1857, the Convention approved the future amendments article, including the periodic constitutional convention clause championed by Traer, by a vote of 21 yeas and 12 nays (63.6%).

Search This Website